Toulouse

Photo: Madame Dulac

Toulouse: La Daurade

Our Lady of Good Childbirth

(Notre Dame de la Délivrance)

until the 14th C.: Our Lady the Brown One (Notre-Dame la Brune)

since the 16th C.: Our Lady the Black One (Notre-Dame la Noire)

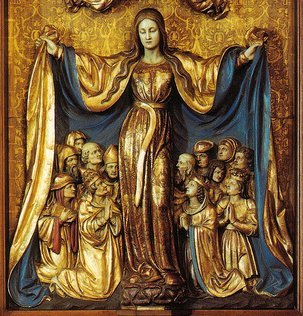

In the Basilica of La Daurade, 1 Place de la Daurade, Haute-Garonne department, Midi-Pyrénées region, an 1806 reproduction of a much older statue destroyed during the Revolution, painted wooden bust, dressed up to look like a full size statue.

'Daurade' is a kind of fish and must be one of the strangest nick-names for a statue of the Blessed Mother. Yet it was skillfully chosen, because everybody will ask: "Why is Our Lady called La Daurade?" And then this ancient story has to be told from generation to generation:¹

In 109 B.C. the Roman Consul Servilius Cepio drained the lake of Toulouse in search of the famous 'gold of Toulouse' that the Gauls had stolen from Delphi. Instead of discovering a worldly treasure however, the statue of a Dark Mother was found floating in the draining water. She was revered as a Pagan goddess until it was decided in 415 A.D., when all Pagan worship was outlawed, that she was really Mary the Mother of God.² The present, late 18th century incarnation of her church still stands where the lake once was, on the banks of the river Garonne.

The statue known as the Brown One was stolen in the 14th century and replaced by a copy, which later became known as the Black One.

The Belt of the Black Madonna

Notice the inscription under La Daurade. It says in French: "Receive and wear this blessed belt as a sign of my maternal protection and as a pledge of a happy delivery." It refers to an ancient custom still practiced in Toulouse to this day: that of borrowing a belt or a piece of fabric from the Holy Virgin to lay it across the belly of a woman in labor. During the Middle Ages la Daurade became so famous for helping women in childbirth that Toulouse became a major pilgrimage center of France, sought out in particular by pregnant women.

According to Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, it was an ancient Pagan practice to borrow a belt from a goddess and tie it across a woman’s belly during childbirth in order to ensure a quick and painless delivery. Both Isis and Hera were known to lend out their belts,³ and so was Mary. The “real” belt of the Virgin was venerated in Marsat (another Black Madonna shrine) since at least the 6th century, but only queens and princesses dared to borrow that one. Other women had to content themselves with the belts or mantels of miraculous statues of Mary, like la Daurade or the Black Madonna of Thuir.

According to Michel Dagras the custom in Toulouse began with not only women in labor, but also sick people being covered by one of the mantels of Mary. You see, every famous Madonna statue had a great wardrobe of precious mantels that the faithful would offer her. Just like the priests, she had different color outfits that changed with the liturgical seasons of the church. Old mantels might get cut into several pieces so as to go out to more patients. Mary’s mantle stood for dignity and protection from evil. Under it the faithful hoped to share in their Mother’s dignity and to be protected from their own inner as well as outer evil. For centuries, the ‘Madonna of the protective mantel’ was a common “type”, i.e. a recurring theme in Catholic iconography.

The 15th century Austrian painting on the right is a great example: all of Christendom of the time, Pope and king, clergy and laity, rich and poor gather under Mary's mantel. An angel tries to shoot arrows of justice at the crowd, but they break on her mantel.

Well, with so many people wanting to get under a mantel of the Black Madonna of Toulouse there weren’t enough to go around. To make matters worse, her whole wardrobe was burnt during the Revolution. That’s when the Church resorted to mass producing belts that would be consecrated to the Virgin by praying and touching them to the miraculous statue for a while.

To this day a priest at the basilica will individually bless such birthing belts for specific women to help during labor. A mother will obtain the belt for her daughter, just like her mother did for her.⁴ They do so well before the baby’s due date so that wearing the belt keeps reminding the mother to pray Mary for grace. The white satin belt with an image of the Black One on it comes in an envelope together with a picture of la Daurade, a medal of her that one can wear, a candle to light as a symbol of one’s faith and prayers, Marian prayers such as the rosary and the Magnificat, as well as instructions on how to use the belt properly. They say: “What does the sign matter? Belt, medal, or candle are nothing if there is no heart in them! But when one loves, a nothing, a piece of fabric, renders a presence. It’s not magic, it’s prayer.”

If you don’t feel like asking for a belt in the basilica you can see an old one at the National Museum. It is inscribed with the words: “OH MARY, DIVINE MOTHER, PRAY FOR ME. PROTECT ME.”

The Miracles of the Black Madonna

In 1637 the Benedictines in charge of the church of La Daurade composed a book entitled: “Memoirs of the extraordinary things that happen to those who recommend themselves to the very holy Virgin who is conserved in the church of La Daurade in Toulouse.” According to this book La Daurade protects not only women in childbirth, but also those who fight for the Catholic faith, as well as all in need.

In 1631 when the Black plague was threatening the city, the inhabitants staged an elaborate procession of the Virgin called, ‘The descent of Our Lady the Black One.’ After that descent from the high altar down into the dirty streets, the disease gradually disappeared. From then on, whenever there was a serious calamity threatening Toulouse, whether drought or flood, the people brought their Dark Mother to descend among them.

But one day, on 8/18/1672, a terrible fire broke out outside of Toulouse. When it had destroyed 200 houses and was threatening the palace of parliament and the whole city, the archbishop armed himself with the Blessed Sacrament (i.e. a consecrated piece of bread that Catholics believe to carry the real presence of Christ). He personally took it to the place of destruction, all the while asking Jesus to put out the fire. To no avail; the fire raged on. So the faithful decided to bring out the Black Madonna instead. As soon as she arrived at the fire the wind changed and the flames quickly died down. Hmmm…. No one believed this was a coincidence, but what did it mean? To this day the theologians of Toulouse try to find an acceptable explanation.

There is a mostly lovely article by Michel Dagras on the website of the Association for the Promotion of the Patronage of la Daurade in Toulouse entitled “Notre-Dame la Noir: pourquoi la ceinture?” Therein he warns not to take this event as proof that Mary is more powerful than Jesus and admonishes the faithful always to put Jesus before Mary. Yet he doesn’t offer any explanation.

So let me try. Perhaps we have a situation like the wedding at Cana (John 2:1-11) where Mary reported to Jesus: “They have no wine” and his response was not very compassionate: “Woman, how does your concern affect me?!” John’s Mary didn’t take no for an answer, but coerced her son into performing his first public miracle. To many this means that while our Savior died for the ultimate salvation of our souls, the nitty gritty problems of daily life in the world are better presented to our divine Mother, who cares for us on that level. Just like human mothers and fathers may play different roles in a child’s life, all of them being important, so too do Mary and Jesus.

However, to the devotees of Mary she is not only good for practicalities; she is their co-redemptrix, i.e. she together with Jesus redeems their souls. Maybe Jesus was more powerful in that regard to begin with, but according to what Mary says in many apparitions (including in Fatima) God decided to give equal responsibility for souls to Mary and Jesus. He seems to want them to work as equal partners. What if God the Father decided to leave the quenching of the fire in Toulouse up to Mary rather than Jesus, because he wanted his Church to heed the fifth commandment: “You shall honor your father and mother.” (Exodus 20:1-21) It doesn’t say anything about honoring one less than the other. In my experience they are like two sides of one coin.

More History

The history of La Daurade is inseparable from a famous confraternity founded in Toulouse in 1323 under the name of "Company of Gay Knowledge" (Companie du Gay Scavoir). Outwardly it was an academy that staged championships of troubadour poetry honoring the feminine in its pure earthly and heavenly forms. Their songs were full of praise of the Black Virgin and a mythical Lady Clémence Isaure, supposedly their founder and the ideal woman, a wonder of beauty, intelligence, and nobility. According to Jacques Huynen however, she really denotes Isis and all the children of the goddess who have realized the highest esoteric knowledge through a path of secret initiations.⁵

In 1790, during the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution, Our Lady the Black One's triumphant processions were outlawed and the statue placed in a museum. After five years the secular authorities graciously decided to allow the statue's return to her church. But they didn't expect anything like the huge fervent crowds of faithful that pressed around their Mother. Horrified, they ordered the precious Madonna to be destroyed after all. It took another 12 years, till 1807, before a copy could be made and safely innstalled in her church. The event was celebrated again with a great processsion and to this day the cult of la Daurade is very much alive.⁶

Footnotes:

1. Others claim the name is a French pronunciation of the Latin "deaurata", gold-plated as in the decorations surrounding her. Maybe they'd rather forget the Pagan roots of their divine mother?

2. Ean Begg,The Cult of the Black Virgin, London, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1985, p. 229

3. Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, Vierges Noires, Editions du Rouergue, 2000, p. 146

4. Sophie Cassagnes-Brouquet, p.200+201, and Jacque Huynen, L'Enigme des Vierges Noires, Editions Jean-Michel Garnier, Chartres: 1994, p.201. (Not a mistake, both books happen to treat La Daurade on page 201.)

5. ibid., p.202-3

6. See Madame Dulac's fantastic site on sacred sites, which includes lists of Black Madonnas by departments of France.