Custonaci

Maria Santissima di Custonaci, Patroness of Custonaci, Erice, and Valderice, Madonna of the Water (Madonna del Acqua)

In her sanctuary Maria Santissima di Custonaci, Piazza Santuario 1. The town lies 1 ½ hours West of Palermo, Sicily. Painted on wood probably by an artist of the Flemish school , 15-16th century.

Here we have yet another whitened Madonna, before and after renovations. Some locals still call her black while others don’t. In 1993 Lucia Birnbaum remarked with relief that this Madonna had remained black.¹ (I guess she didn’t knock on wood…) The renovation was performed around 2005. While it lightened her complexion, it also brought a very important element to light: the wheat. Naked Baby Jesus holds three sprigs of it, a triple symbol for bread and the earth, while Mary’s mantle is decorated with vases holding seven sprigs. Note how the renovation before the last took pains to cover that wheat up. It replaced the decorations on Mary’s mantle with a meaningless leafy design and adorned the Mother with jewelry that covered the wheat in the hands of Baby Jesus. Why go through such pains to cover something up? Here is why:

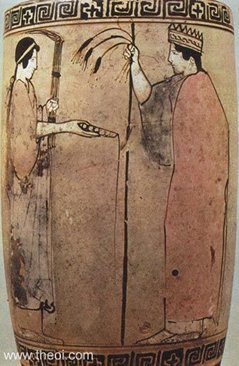

Demeter (right) holds a royal scepter and sheaf of wheat. Persephone (left), holds an Eleusian torch and pours libations from a cup.

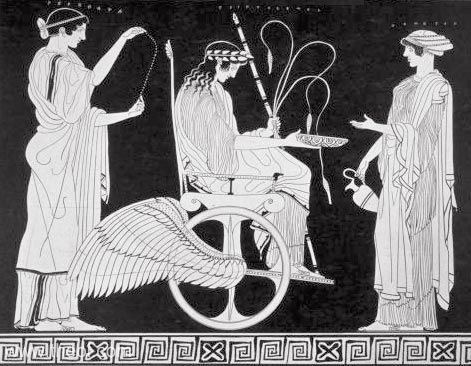

Demeter and Persephone bid the young demi-god Triptolemos adieu and send him off with their gift, the knowledge of growing cereals, to spread it around the world. Copied from a vase from about 450 B.C.E.

Mary, the Earth, and Demeter

Brigitte Romankiewicz explains that the type of Madonna called ‘Madonna in the wheat dress’ (Madonna im Ährenkleid) spread throughout Europe in the 14th century. But in the 6th century Mary was already referred to as the fertile field which brings forth the wheat (baby Jesus) for the bread of life (the crucified and resurrected Christ). This symbolism, she says, clearly connects to pre-Christian thoughts about the child of the light (often represented by a golden head of wheat) coming forth from the dark womb of God/dess (shown as the dark mantle of Mary).²

Now you may wonder: “Was pre-Christian thought still alive in the 15-16th century, when this Madonna was painted?” Certainly it had been suppressed for a long time, but remember: this was the Renaissance, the rebirth, or return to romanticized Greek roots of European sophistication. Everybody knew that those roots included honoring a divine feminine. The renaissance was also intent on a renewed unabashed appreciation of the body (hence the naked child and nursing mother). The argument was that according to the Bible (Genesis 3:7) the need to cover one's nakedness didn't arise until humanity's fall into sin. It follows that those who are free of sin, like Jesus and Mary, don't feel a need to hide their bodies.

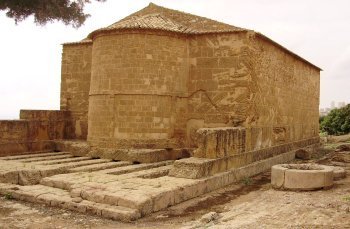

All that is left of Demeter's temple in Enna

“Good Catholics” would likely interpret the wheat as pointing solely to Jesus becoming our bread of life. But why then cover it up? Especially in Sicily wheat is inextricably connected to the Greek earth-goddess Demeter, who was venerated there as the goddess of grain, for many centuries. Sicilians proudly proclaimed that she dwelled on their island, in her great temple in Enna, overlooking the whole isle. (Of course, Greece, Egypt, and Crete also professed to be her homeland, but that’s beside the point, right?) Only the foundations of this temple in Enna are left, but Demeter lives on in the half subconscious memory of the Sicilians. She taught humanity to grow wheat and so wheat was Sicily’s gift to humanity. It is present everywhere: on Sicily’s flag and as an offering to Jesus and the saints in churches, homes, and bars.

A street shrine to San Calogero in Agrigento

In her wonderful book “No Pictures in My Grave: a Spiritual Journey in Sicily” Susan Caperna Lloyd relates the various ways in which ancient goddess rites linger in Catholic traditions.³ She mentions that until the late 1800’s a statue of Demeter holding Persephone stood on the altar of the Catholic church in Enna. An old sacristan comments: “But when the Pope found out, he made the people take the statues down … now we have the Madonna and her child. But to me, it is the same thing.”

Caperna Lloyd also describes the “bread ladies” of San Biagio, who bake religious bread ornaments for special holidays. She found that at least some of those women publicly acknowledge that their custom has its roots in ancient Demeter rites, even if the tradition has long become part of Christian celebrations.

The official guide book of the Valley of the Temples in Agrigento includes a chapter on Demeter and Christian practices in Sicily. It says that the origins of Demeter are rooted in older forms of the Great Mother and that the offerings of wheat and bread that used to be brought to the Goddess are now given to Christian saints. In Agrigento it is Saint Calogero, whose followers throw bread rolls containing fennel seeds at his statue during the processions of the saint.⁴ Interesting how dark Mother Earth was replaced here buy an old black monk who is famous for helping the poor during the plague.

Another saint whom the Sicilians seem to link with Demeter is San Biagio (St. Blase) an early bishop and martyr. He was famous for healing not only humans but also wild animals who would gather at his cave. The above mentioned “bread ladies” live in a town called after him and in Agrigento a church of San Biagio was erected on the foundations of a temple of Demeter. It was built in such a way that the place where the “holy of holies” of the old temple used to be was left uncovered, with two round sacrificial altars next to it still in place. It’s as if two groups agreed to share this space: Christians and the worshippers of Demeter. It reminds me of Northern California where Buddhists meet in Christian churches and some churches serve as synagogues on Fridays. It seems to me that many European Catholics appreciate that their roots reach into the ancient, even if pre-Christian, past. It's all still part of who they are and the divine by so many different names is still the divine…

San Biagio on foundation of Demeter temple in Agrigento

Sacrificial altars of Demeter next to church

But back to Custonaci: According to Ean Begg the Madonna of the Water is attributed to St. Luke,(*5) but none of the more recent Italian internet sites claim that, nor do the locals know her by that title. Instead they tell this story:

Some time in the 16th century a French ship was in grave danger of a fatal wreck. The crew invoked the Madonna before an icon they were carrying on board and miraculously they were rescued. When they anchored safely in the bay of Cala Buguto and came ashore in Cornino, Custonaci, they felt obliged to donate their Madonna to the local community and to build her a sanctuary there, in commemoration of their rescue. So since she came to her children from the sea she may have been called Madonna of the Water.

In recognition of her many miracles the Vatican allowed her official coronation in 1752. Photos by Schano

Her landing is reenacted every year and, as you can see below, the whole town shows up for it. The festivities last three days: the last Monday through Wednesday of August. Monday at sunset her ship lands, surrounded by a procession of fishing boats. As the sacred image comes ashore, it is greeted with fireworks and then solemnly processed to its church. Tuesday is a holiday and Wednesday the (once) Black Madonna is carried in a magnificent procession through the streets of Custonaci.

Tips for the traveler:

1. From the Sanctuary of the Madonna of Custonaci a 4 km long pilgrimage path leads via a 9th century village and living history museum at the mouth of the cave called Mangapane to the Cave of the Crucifix. It’s a beautiful nature hike. You can drive as far as Mangapane.

2.Custonaci lies near Erice, which was famous for centuries for its great temple of Venus. The Romans remodeled it, but it had already been a holy site of a fertility goddess since at least the 7th century B.C.E. The little that remains of it lies inside the Norman “Castle of Venus”. Although the sacred well of Venus now runs dry many couples still choose the place to get married. Even Christian newly weds come here for a blessing from the Goddess of Love after they get out of church.

View from Venus temple over the Norman castle with the Mediterranean and the Egadi Islands in the background

The sacred well of Venus in Erice now runs dry.

Footnotes:

1. Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum, Black Madonnas: Feminism, Religion & Politics in Italy, Northeastern University Press, Boston: 1993

2. Brigitte Romankiewicz, Die Schwarze Madonna: Hintergruende einer Symbolgestalt, Patmos Verlag, 2004, p. 197

3. Susan Caperna Lloyd, No Pictures in My Grave: a Spiritual Journey in Sicily, Mercury House, San Francisco: 1992, p.55

4. Archeaeological and Landscape Park of the Valley of the Temples, The Valley of the Temples of Agrigento, Agrigento: 2008, p.115

5. Ean Begg, The Cult of the Black Virgin, Arkana: 1985, p. 241