Kirchwald

Madonna in the Kirchwald

St. Mary in the Kirchwald

In the pilgrimage church and hermitage Kirchwald Mariä Heimsuchung (the visitation of Mary), that lies in the woods, at about half an hour walking distance from: 83131 Nußdorf am Inn, in Bavaria. You can drive to it on the Mühltalweg, but that is frowned upon. Pilgrims are expected to do the hike up the mountain to visit their divine Mother. 16th century copy of a 13th century Byzantine (Eastern Roman empire) icon attributed to St. Luke, tempura colors on a thick, wooden board.

image: a holy card available in the church. All other photos: Ella Rozett

A Black Madonna?

A beautiful booklet for sale in the church (1997 edition) says a lot on its pages and between the lines. It informs us that this miracle working ‘Gnadenbild’ (image of grace): “is without a doubt a very exact copy”. (p.26) That would include an exact copy of the skin color. She must have been a Black Madonna even though she has never yet been called that! On the contrary, her Blackness is hidden and explained away wherever possible. Much points towards her devotees’ discomfort with her dark face.

None of the websites about the pilgrimage church of Kirchwald show the original but instead a White rendition. One example: http://www.pilgerzeichen.at/lexicon/index.php?entry/197-kirchwald-bayern/

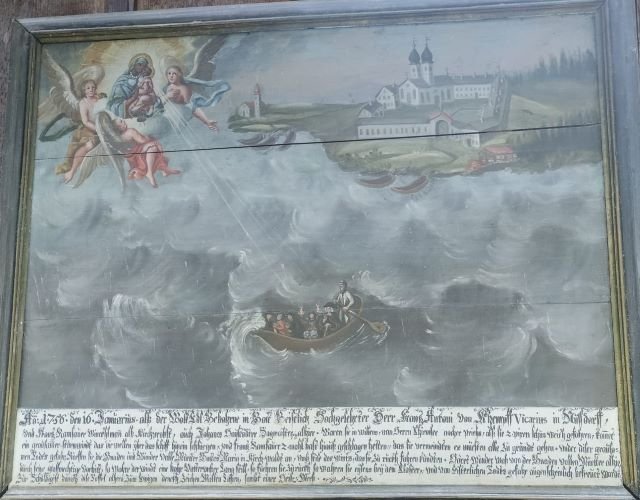

2. The church owns a beautiful collection of ex-voti, i.e. paintings offered to the Madonna that tell the story of a miracle received. In 2/3 of those exhibited in the church she is portrayed as White.

3. The above-mentioned booklet does acknowledge that she was brown from the beginning but claims that she further darkened “significantly” because of the varnish applied to her, a mix of linseed oil, sap, and amber. (p.28) the Wikipedia article on varnish explains: “Early varnishes were developed … to get the golden and hardened effect one sees in today's varnishes. Varnishing was a technique well known in ancient Egypt.” Therefore, countless other paintings of that period that depict White people would have been treated with the same kind of varnish without it turning them black. She may well have darkened, but she must have been dark brown to begin with.

4. There are frescos on the ceiling that praise Mary. The booklet includes a hymn that explains the frescos. Two of the verses praise her whiteness. She is “pale as the lily, snow white in her chastity, beautifully white as a pearl in her immaculately pure conception”. (p.16) Strange somehow that in the presence of a Black Madonna they would put so much emphasis on how very White her beauty and purity are. At least they didn’t lighten her when they cleaned her in 1995. Thank God for that!

Her devotees haven’t given her the title she deserves, but I will. She is a Black Madonna! Not only because her skin is black but also because she meets so many other criteria that constitute a Black Madonna: she works miracles, she has a holy spring, an ancient heritage, and she is a copy of an icon attributed to St. Luke, many of which are Black Madonnas.

The Image

This image of grace is of the icon type called Eleusa, which in Greek means ‘tenderness’ or ‘having mercy’. Madonnas of this type are called Our Lady of Tenderness in English and always show Mary and Jesus cheek to cheek and holding hands. The gold ornaments on her right sleeve bear the inscription: “mater dei ora pro nobis” (Mother of God pray for us).

Mother Mary is often portrayed with one star on her cloak at the level of her forehead to denote her virginity. In this icon there are three stars on her robe, pointing to the tradition that she was a ‘perpetual virgin’ before giving birth to Jesus, during, and after.

Until 1874, the icon was adorned with silver hearts on the chests of Mary and Jesus and richly ornamented halos. Even though the booklet explains that such ornaments were only applied to highly venerated ‘images of grace’, they were removed during a renovation in 1874. The old ex voti usually show the silver hearts. It’s sad that people were fond of those kinds of details, but 2/3 of them chose to ignore her Black skin and portrayed her instead like they wanted to think of their divine mother: lily White. As if a Black Mother of God couldn’t be the epitome of beauty, goodness, and purity!

The History

The story of this pilgrimage church began in 1643, when Michael Schöpfl, a weaver journeyman from Iglau, (modern day Jihlava in the Czech Republic) went to Rome. A journeyman is fully trained in his craft, but not yet a master with his own shop. Journeymen traditionally went on their ‘wander years’ as part of their quest for their own home and business. Michael Schöpfl was the son of German, Lutheran parents and had heard much about the pope and his ‘capital of the world’. He wanted to go see for himself what it was all about. Apparently, the Catholic Church made a big impression on him and he on it. The following year he converted and was baptized in St. Peter’s cathedral. (It doesn’t get any more Catholic than that!) When, after three more months in the ‘eternal city’, he decided to go home, a cardinal presented him with this valuable copy of a Black Madonna attributed to St. Luke the evangelist and some relics.

His return voyage took a dramatic turn when he fell into the hands of violent recruiters for some local army in Northern Italy. He had no intention of joining any army other than perhaps God’s, but they took him by force and inscribed him. After many days, he was able to flee, but was captured the same day and sentenced to death by hanging for being a deserter. The latter was already set against the gallows when he prayed and promised God: “If you spare my life, I will consecrate it to you and spend the rest of it either in a monastery or a hermitage as a servant of Jesus and Mary.” His prayer was answered when the abbot of the local Dominican monastery saved him by some trick. But did he want him to join his monks? Oh no! Countless monasteries in Northern Italy came up with “various pretenses” why they couldn’t take him and his Madonna in. You see, at the time, the vast majority of monks and nuns were still aristocrats. Poor folks could join as “lay brothers and sisters” and spend their days doing the manual labor for the aristocratic monks and nuns, who got to actually pray and contemplate scriptures. Once in a while, a commoner may have been allowed to join a monastery, but he or she would need to present a sizable dowry. Apparently, the Black Madonna, the relics, and the weaver convert didn’t quite cut it.

On September 21st 1644, Michael Schöpfl came to Nussdorf in Bavaria and felt a strong desire to settle there. So he climbed the next best mountain and found a tiny cave in the Kirchwald, which means Church Forest. It was already called that at the time because the people of the neighboring village had to traverse it to get to church. He got permission of the local community and Church authorities to build himself a tiny hut next to the cave, where he would spend the rest of his life. He built a separate little hut for his Madonna.

The new well that was dug to provide water for the hermitage looks holy in its little chapel, but is not the original holy well, which sadly dried up around 1930 and not a trace of it remains.

Near his poor little hut and crack in the rock there was a spring, which was reputed to be bad for humans and cattle alike. Brother Michael needed that water to be potable and was determined to transform its character. He channeled it into a well he built for it, made a vow and went on pilgrimage to the Marian shrine and healing well in Högling-Weihenlinden (about 40 km to the North West, an ancient holy place that had 2 sacred trees, besides the healing well and miracle working Mary statue). He brought water from there and poured it into his well, placed the relics he was given in Rome into it as well. Then he prayed fervently to Mary that she may make the water potable. She more than answered his prayers. “It was as if the praying hermit had poured, along with the healing waters, also the mercy of Mary Mother of God into his well.”(p.5) Soon miracles began to be granted through the water and through the image and the faithful came from near and far to be healed in body and soul. Since the way to his cave and tiny chapel was treacherous, he built a small, more easily accessible 6 x 6 wooden chapel further up the hill. That remained the only chapel there until his passing 23 years later. Very soon after his death, construction of a bigger, more sturdy church was begun, financed and built by pilgrims and volunteers. When that too became too small and started falling apart, the present church was built.

To this day, a hermit lives here and is happy to counsel pilgrims and give visitors a thorough tour. You can knock on the door of the hermitage, which is rather big because in the olden days, the hermits were obliged to run a little school in exchange for the support they received from the village.

Brother Damian belongs to an order of hermits. Beautiful frescos in the entry tell the story of the Black Madonna coming from Rome to Bavaria.

Miracles galore

Michael Schöpfl and all his successor hermit caretakers of this holy place kept exact records of all the miracles wrought there until the year 1756. The church also accumulated the biggest collection of ex voti in the area. Within 200 years, 100 paintings telling of the Madonna’s miracles were collected. Sadly, about 40 of them were stolen in 1975. Of the ones left, only those including a proper date and description of the miracle were hung in the church. Here are some of the beautiful stories listed in the annals:

In 1646, St. Mary in the Kirchwald straightened the crooked limbs of a little girl.

In 1652, Apollonia Huberin in Tyrol suffered unbearable headaches and fever. When no medicine could help her, she took refuge in the Mother of God of Kirchwald and had water from her healing spring brought. As soon as she drank it, all pain and danger disappeared.

In 1721, Michael Niederdanner fell out of a walnut tree. He was carried into his house without any signs of life. But when his brother made a vow before the Madonna in the Kirchwald, he regained perfect health.

In 1745, the estate of Anna Raechlin am Draexl zu Sonnhart was ransacked by a Hungarian troop of 30 horsemen and 15 foot soldiers. They stole 14 cows and set fire to the house. But when Anna made a vow to the Madonna in the Kirchwald the fire did no damage and the cows all came back.

In 1754, Anna Sigling from Rossersberg had such pain in her eye that she thought she was going blind. When she “carried her trust to the Mother of Grace” and washed in her spring, she was healed. The same Anna had already received a healing of a very painful arm from Mary’s waters.

On June 10th 1754, the 6 months old son of the wood miller Johann Hausstaetter, fell into the mill creek, was twice tumbled through the water wheel, and floated 150 steps. When he was pulled out, there was no sign of life in him. The distraught parents carried the baby home and begged the Mother of God of Kirchwald with all their hearts for their child’s life. With that, the child opened its eyes and began to live again.

In 1766, She stopped a raging wildfire that was quickly moving towards a village.

To this day, there are reports of miracles.

3 Golden Saturdays in Honor of the Mother of God

The custom of honoring the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturdays (sabbath day) probably goes back to the earliest centuries, though we only have written evidence of it beginning in the 8th century.[i] The 3 Golden Saturdays began as Golden Saturday Nights celebrated at midnight with a vigil mass. They are first mentioned in writing in 1387. (p.29) On the 3 Saturdays following the feast day of St. Michael the Archangel, September 29, great crowds of the faithful would gather at a holy shrine of Mary, go to confession, drink healing waters, receive communion, ask and often receive miracles. They would leave their homes during the night, crossing mountains, fields, and forests by the light of burning torches.

In Kirchwald, it often took 10 to 12 priests hearing confessions and celebrating mass from Friday night or dawn on Saturday and all day, 3 weeks in a row, to cover all the people who wanted full dispensation, i.e. to be sure that they were going straight to heaven at the time of their death. People felt purified and filled with new strength for their lives and celebrated with much food and drink up on that mountain. Among all Marian holidays, these Golden ones ruled supreme, spurned on by the pious Emperor Ferdinand III (ruled 1637-1657). When he had asked Mary to tell him how he could best honor her, she appeared to him in a dream and said: “Know that whoever will honor me piously with three Saturdays after the feast of the archangel Michael does me a most pleasing service. That person can be sure of my motherly grace and be consoled by the assurance that I will stand by them motherly during their lifetime and in the hour of their death will protect them faithfully against the power of hell.” (p.31) On the first Golden Saturday, Mary was honored as the daughter of our eternal father; on the second Saturday as the virginal mother of her divine son, on the third Saturday, as the bride of the Holy Spirit. She was asked for the ‘gold coin’ of love for God and neighbor.

the back of the church of Maria im Kirchwald with the hermitage-school on the right

[i] For a full account see the article Saturday Devotions in Honor of Our Lady on the University of Dayton website.