London, St. Dunstan-in-the-West

The Black Madonna or the Red Madonna

In the church St-Dunstan-in-the-West, 186a Fleet St. Holborn, London EC4A 2HR, UK

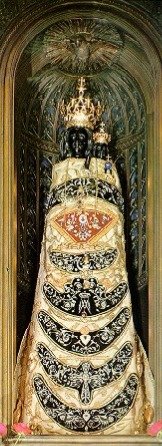

In 2019, Sarah Bisby, a member of an internet chat group called “Reflecting the Black Madonna”, discovered this fascinating Black Madonna in the heart of London and brought it to my attention. Since nothing is written about her anywhere, I emailed the Anglican parish, asking what they could tell me about her. In short order, I received a very friendly response from the parish administrator Rebecca Haslam, which red: “What I do know about the “Black Madonna” – as we call her informally – is that she was originally the “Red Madonna”! By this I mean that her dress was painted red – you can still see the flecks of red paint on her knees – but this color was worn away many years ago, revealing the dark wood underneath – turning her into the Black Madonna. The Madonna also had a tall gold crown, which rested in the smaller pointed wooden crown which she still wears. Again, this disappeared a long time ago!”

Since this beautiful Black Madonna was until now completely unknown outside of her parish, my guess is that she is a copy of Our Lady of Walsingham, whom she resembles a lot, only missing the lily in her right hand. Walsingham is known as “England’s Nazareth” and is the most important Marian shrine in Great Britain since the 11th century.

Both Madonnas are of the type called ‘Hodegetria’, which is Greek for “she who points the way” or “the guide”. The Church’s idea is that Mary points to Jesus as the way to Heaven. Actually many of the images portray both of them pointing to each other as the way.

The first and most famous Madonna Hodegetria was venerated in Constantinople from the 5th to the 13th century. She was said to have been painted by St. Luke the evangelist while the Virgin Mary sat portrait for him in her house in Nazareth. (It makes sense that Our Lady of Walsingham is of this type since her shrine is said to be a replica of Mary’s home in Nazareth.)

When I shared the answer I received from St. Dunstan-in-the-West with the online Black Madonna chat group, Sarah’s response was: “I wonder if she had any menstrual connection.” I had heard of “menstrual connections” to black Madonnas, but had found the research unsatisfactory, with the conclusions too far ahead of the evidence presented.

Nevertheless, contemplating this Black and Red Madonna, it hit me: they have a point! After all, Mother Mary in general and the Black Madonna in particular are routinely invoked for conception and in childbirth (e.g. in Nuria and Toulouse). Why shouldn’t she also have a “menstrual connection” when even Jesus has one! All three synoptic gospels tell the story of him healing the woman who couldn’t stop bleeding for 12 years.

The Mother of God who shows the Way certainly has a strong connection to the color red. If you image google Theotokos Hodegetria (the Greek translation of this title of hers) you will see lots of red robes and mantels. It seems that this echoes an ancient tradition. The Wikipedia article on “Hodegetria” quotes several ancient sources that recount the following ritual: Every Tuesday twenty men come to the church of Maria Hodegetria; they wear long red linen garments, covering up their heads like stalking clothes … there is a great procession and the men clad in red go one by one up to the icon; the one with whom the icon is pleased is able to take it up as if it weighed almost nothing. He places it on his shoulder and they go chanting out of the church to a great square, where the bearer of the icon walks with it from one side to the other, going fifty times around the square.”

Now what is so important about the color red? Stefan Brönnle explains in his article: “Rote (i.e. red) Madonna”: “In Christian color symbolism red is the color of blood, of fire, and of the Holy Spirit. With it Mary clearly becomes the figure of the “God bearer” (i.e. theotokos/Mother of God), she is the Christian version of the red goddess, the goddess of fertility and life force.”¹

As Margrit R. Schmid says in her documentary on SRF, the Swiss public broadcasting Co. “Schwarz bin ich und schön”, the red triangle and black moons on the robe of the Black Madonna of Loreto are pre-Christian symbols of fertility goddesses.

When modern Westerners hear the term “fertility goddess” we think goddess of sex and procreation, but actually there was much more behind it. Fertility meant the power to bring forth life, to create. In the ancient mind what we call “fertility goddesses” were more like creator goddesses. And the power to create was intimately linked with red menstrual blood. Why?

Because from pre-historic to ancient times, it seems that people didn’t know that men had any role to play in procreation. Instead, it was thought to be effected by the collaboration between women and the divine. It was widely believed that the fetus was formed out of menstrual blood and imbued by the divine with the breath of life.²

The supra human power of menstrual blood was further perceived in the fact that the moon would disappear, women would bleed together, and with that the moon would begin to reappear.³ The synchronicity of women’s cycle and the lunar cycle couldn’t be a coincident! Hence women were perceived to have incredible power and their menstrual blood was the sign and place of it.⁴

My theory is that once men figured out that they actually did have a role to play in procreation, they literally made the fatal mistake of wanting to imitate the power of menstrual blood with blood procured from animal and human sacrifices. Bad decision. Why didn’t they celebrate the power of their semen? The notion that power came from blood and pain (of menstrual cramps and childbirth) must have been too entrenched in the human psyche by then.

Besides the red of menstrual blood, another symbol links Mary to the menstrual cycle: the crescent moon. Many authors and websites elucidate the connection between the 28 day moon and menstrual cycles.⁵ Because of this connection, which is at least a synchronicity, i.e. a "meaningful coincidence", the moon became the foremost symbol for femininity and the Goddess. Mary inherited this symbol, along with many others, as well as countless titles, from her pre-Christian sisters in the realm of divine mothers and Queens of Heaven.

St.-Dunstan-in-the-West, home of the Red and Black Madonna

So do Black Madonnas in general have a ‘menstrual connection’? I would say, not directly, only insofar as Mary in all her forms has a connection to pre-Christian goddesses, who in turn have a menstrual connection. But this particular Red and Black Madonna may well have a more direct connection. How did her red color come off? My guess is by the faithful rubbing it off. I’ve seen the parts of the Black Madonna of Montserrat that stick out of her glass case rubbed and kissed till they were white, only to get painted black again, ready for more kissing and rubbing. This touching of sacred images in order to absorb some of their energy goes back to antiquity. Clergy used to touch cotton balls to the Hodegetria icon in Constantinople and pass them out to people, so that they could take her blessings home.⁶ The faithful in London must have really been after that red color to rub it off so completely. It must have carried a blessing they wanted.

Did they think: “I want to get some of that red paint on me, because it is a faint remnant of the super powerful menstrual blood of the goddess.”? Not likely, but that’s the beauty of the Church to me: it has preserved some ancient practices without even knowing why and without being conscious of how far back into prehistory they go. E.g. dressing Madonnas so they form a triangle. I believe the collective unconscious remembers the triangle as the first symbol of the Divine Mother and maybe even the power of menstrual blood. (More on the “pubic triangle of the goddess” and Mother Mary in my article: “Mother Mary and the Goddess”.)

Footnotes:

1. This is not to say that Madonnas clothed in red always have a “menstrual connection”. In some places and times, red was simply “in”. In 15th century Dutch art it was often used on God Father and Madonnas, because whichever color was most expensive and difficult to produce seemed appropriate for God and the Queen of Heaven. Red qualified. See: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucca-Madonna#Der_rote_Umhang

2. Remnants of this ignorance can be found around the globe, even in the Bible. In Genesis 4:1 Eve makes a “naming speech”, as theologians call it, when she bears Cain, saying: “I have produced a man with the help of the Lord.” Ilana Pardes, author of “Countertraditions in the Bible” has much to say about this.

The best book, in my opinion, in this field is Rufus C. Camphausen’s “The Yoni: Sacred Symbol of Female Creative Power”, Inner Traditions International, Rochester: 1996. On p. 16 he lists two examples of cultures that denied that men’s ejaculations had anything to do with procreation: the Bellonese People of the Solomon Islands until at least the 1930’s and Australian aborigines in north Queensland until the 1960’s. In summary he says: “The basic concept of the prehistoric and ancient worlds was that humans are made from the blood of woman;”

3. Especially in Germany, many are convinced that ancient wisdom and traditions tell us, when women live in close community with each other and in a world without artificial light at night, they bleed together on the new moon. It certainly is a common experience for women who move in together, that their cycles are affected by each other. See: https://www.patheos.com/blogs/starlight/2018/05/the-search-for-a-moonblood-goddess/ and https://gedankenwelt.de/frauen-und-der-mond-den-weiblichen-zyklus-verstehen/

4. An excerpt of Becca Piastrelli’s online article: “Exploring the Menstrual Rituals of our Ancestors”: “In the Hawaiian community before Christianity, menstruation was supposed to be the absolute most sacred time for women. And because it was already a matriarchal society where women generally were seen to have the most spiritual power, it was believed that when women were bleeding, they were so powerful that if men were around them, the menʻs mana or soul energy would just get sucked out because they couldnʻt handle such sacred power.”

In Celtic Britain, to be stained with the red (presumably menstrual blood) meant you were chosen by the goddess. The Celtic word “ruadh” means both red and royal.

The eggs of Germanic Goddess Eostre (womb symbols that have evolved through to modern day Easter) were traditionally colored red and laid on graves to strengthen the dead for the afterlife. In Greece and southern Russia, graves were reddened with ochre clay for a closer resemblance to the Earth Mother’s womb from which the dead could be birthed again.

Celtic rites were often granted by elder women in the community due to the belief that being post-menopausal made you the wisest as you had permanently retained your “wisdom blood.”

As I’ve deepened my own reverence for my moon blood, I’ve been practicing giving it back to the earth each time it comes. There is an ancient Hopi prophecy that states, "When the women give their blood back to the earth, men will come home from war and earth shall find peace.”

5. E.g. The most important and striking symbol though for pre-Christian mother-goddesses and femininity in the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia is the moon with its 28 day cycle that it shares with women’s menstrual cycle. http://ikonografie.antonprock.at/maria-mondsichel.htm

6. See the Wikipedia article on Hodegetria.