Tindari

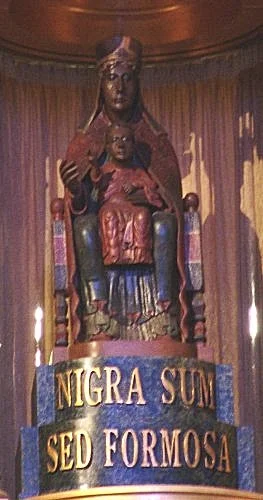

The Black Madonna Santa Maria of Tindari

In her sanctuary in the small city of Tindari, municipality of Patti, province of Messina, on the North-Eastern shore of Sicily, painted cedar wood. Open 6:45 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. and 2:30 to 7:00 p.m. (8:00 p.m. on feast days and in July/August)

The breath-taking sanctuary of this Madonna sits on a high bluff overlooking the sea. It was built on the site of a former temple to Cybele, a goddess who was worshipped in those parts since prehistoric times under the titles Mother of the Gods, the Accessible One, Savior who Hears our Prayers. All the guide books of the sanctuary mention this connection to Cybele. Like I say in the introduction, many in the European Catholic Church appreciate their ancient roots in pre-Christian times. The "Tyndaris" guide book recounts the history of the town from its inception in the 5th century B.C. Emphasis is put on how thoroughly the Muslim invaders of the 9th century destroyed the place. Then it says: "Though life had now deserted this promontory, where oblivion reigned supreme over the ruins of a dead town, in this silence the hands of humble friars, collecting the miserable remains of the once so superb temple of Cybele on the splendid acropolis of Tyndaris erected the first small church of Tindari, on its altar the miraculous statue of a "Black Madonna"."¹

One story says the brown Madonna was brought to Italy in the 8th century by sailors who had saved her from the iconoclastic controversy in Eastern Christian countries. When they drew near to Tindari a storm forced them to take refuge in its bay. Once the winds calmed, the sailors wanted to continue on their way, but the Madonna wouldn't allow the boat to move until she had been offloaded on the beach. From there the local population entrusted her to the little monastery on the cliffs. It seems she wanted to fill Cybele's throne.

Another story reports Saint Mary of Tindari was found by shepherds in a beach front cave, where she had washed ashore in a casket after a long and tumultuous journey. As if to explain and confirm her dark complexion, a note was with her, quoting the same verse from the Song of Songs (1:5) that accompanies so many Dark Madonnas: "I am black but beautiful, O you daughters of Jerusalem." Now the first half of that quote is inscribed in big Latin letters at the base of the statue. Other Latin inscriptions around her throne call her in great mosaic letters: "Mother of Mercy, life, sweetness" - a quote from the prayer that starts with: "Hail holy Queen, Mother of Mercy, our life, our sweetness, and our hope...."

The 1957 sanctuary seen through 3rd century B.C. ruins. photo: Paul Fornaby

The inscription "I am black but beautiful" is significant at a time like ours when so many Black Madonnas are restored to their original whiteness because it is perceived as more beautiful. It seems to say: "Don't mess with my skin color!" To me whitened Dark Mothers are like old women getting a face lift. The Madonna doesn't need a face lift, doesn't need the patina removed. She has darkened for many good reasons. The inscription draws attention to that darkness. Many people don't even register dark statues as "black" because they are used to the natural darkness of old wooden objects and ancient icons due to patina. They look through the statue as through a window into the divine that is beyond shape and color. This is wonderful indeed, but sometimes the statue is like a letter to us from Heaven: the details of the work bear a message to humanity. "Nigra sum sed formosa" also says: "Pay attention to my blackness! Meditate on it!"

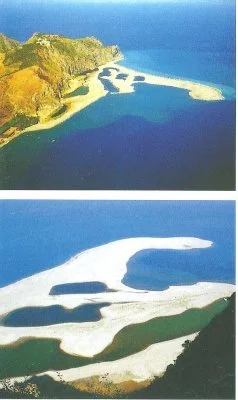

An interesting story is told at the Tindari sanctuary that warns people of prejudiced reactions to dark skin: One day a woman came from far away to fulfill a vow to the Madonna of Tindari for saving her little girl's life. When the woman reached the sanctuary, after a long journey and saw that the Madonna's face was that of a black "Ethiopian" she exclaimed in dismay: "I traveled so far to see someone uglier than me?! The sight of a black slave surely was not worth the discomfort of the long journey!" The moment she expressed her irreverence, her little girl, who had wandered away from her mother, fell from a cliff. The woman called upon the Madonna to again save her child's life. But the miracle had already happened - a sand bank had risen from the sea so the girl could fall on soft sand and live. The woman now believed in the divine powers of the Madonna she had mocked. The sandbank, which stretches 1.5 km into the sea and rises to 4m above sea level is still there today. It changes from year to year with the tides and weather, but often one can see in it the shape of a mother and child. (See photos on right) People say this is to remind us of the miracle the Madonna granted the disrespectful mother.²

Like others, this sanctuary too honors its Madonna with a festival on her birthday, September 8th. Masses are celebrated every hour from early morning to midnight, a procession is held, and fireworks conclude the festivities at midnight.

A freely interpreted "copy" of this Black Madonna is venerated in a small Italian immigrant chapel on Fifth Street in Hoboken, New Jersey. Twice a year mass is celebrated there and every five years, on the weekend closest to September 8th, Our Lady is carried through the streets of the city in procession.³

Though Ean Begg counts the Black Madonna of Tindari among one of those attributed to St. Luke, no one else confirms this view.

Tips for the pilgrim: Look for accomodations in Marinello, the town along the sand bank. There are bungalows to rent from www.camp2relax.nl and a 2 star Hotel Acquarius or up on the hill near the sanctuary in Antica Tindari there's a beautiful agriturismo.

Footnotes:

1. Giuseppe Tornatore, Tyndaris, Edizioni Tornatore, Messina, p. 50

2. See: ibid. p. 58 and Mary Beth Moser, Honoring Darkness: Exploring the Power of Black Madonnas in Italy, Dea Madre Publishing, Vashon Island, WA: 2005, pp.70 + 73

3. Joseph Sciorra, The Black Madonna of East Thirteenth Street, in: Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore, Vol. 30, spring-summer 200