Altötting

Photo: Ella Rozett

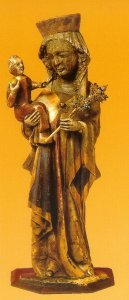

Our Dear Lady of Altötting

(Unsere liebe Frau von Altötting)

On the Kapellplatz (plaza of the chapel) in the heart of town, about 1 hour from Munich, Bavaria, around 1330, 64 cm painted linden wood.

Tradition recounts that the site of Our Dear Lady's 'chapel of grace' was already holy ground before the area was Christianized. As so often, the link between that era and Christian times seems to have been a tree, and the Black Madonna bridges the gap between sacred tree and Christian altar. Many Black Madonnas are venerated in places that were sanctified by a sacred tree or appeared in a tree.¹ To this day several centuries old "Marienlinden" (Mary-linden-trees) are venerated in Germany and Austria.²

Our Dear Lady of Altötting was carved of linden wood and a guide to the town speaks of a venerable, ancient linden tree that might have played a role in the town from its very beginnings. Some pre-Christian tribes in Germany venerated the linden tree besides the oak as sacred.³ While the oak was dedicated to Thor or Donar, the male god of thunder, Freya, the goddess of love, was worshipped in linden trees. Legal matters, public concerns and disputes were decided under linden trees in hopes that the goddess would provide an aura of charity, truth, and reconciliation. That’s why these trees were called ‘trees of justice’. The places where they stood were called Thingplatz, i.e. an outdoor place for important public gatherings of the tribe centered around a linden tree.

Altötting's linden tree stood next to the chapel and was already hailed as ancient in 1542. In 1674 it was cut down "among great grumbling of the people".⁴ It was to make room for a big, baroque basilica that was to encapsulate the 'chapel of grace', but the project was ill-fated. Lacking the support of the people since the sacrifice of their beloved tree, it ran out of money and was abandoned after the foundation was built.

Centuries later a new tree was planted in the same place and trees mark the outline of the failed basilica. Not only that, in 1980 no other than Pope John Paul II planted a linden tree (the "Pope-Linde") in front of the monastery of Altötting's saint Brother Konrad. This is the same pope who apologized for the crusades, the inquisition, and any other misconduct he saw in the history of his Church.⁵ Was this planting to make amends to Mother Earth for the many sacred trees that fell victim to Christian axes?

A Mary-Linden-Tree in Sulzberg, Austria with a Madonna and child in the hollow of the tree. Photo: Reinhard Aill Farkas

Altötting's chapel of the Black Madonna is the oldest Christian site in Bavaria. It dates back to 680 when St. Rupert baptized the first Christian duke of Bavaria at this holy place. In commemoration of this pivotal event (and probably in order to convert the Pagan into a Christian sanctuary) the duke had an octagonal baptismal chapel erected and placed a Madonna in it.⁶ The original chapel was destroyed, but rebuilt. The present one is estimated to date back about to the year 1000. It is now the church tower and heart of the sanctuary. A nave for services and a gallery were added in the late 15th century. The gallery, a porch that wraps around the whole building, houses hundreds of ex-voti, which cover the walls and ceiling. There is not an inch left for more of these illustrated miracle stories. It's an impressive testimony to Our Dear Lady's power and compassion, as well as the faith and gratitude of her devotees.

In 907, Altötting was ransacked by the Hungarians and laid waste for 300 years. According to a well known court historian by name of Johannes Turmair, aka Aventin (1477-1534), only the chapel of "the virgin God-bearer" survived the attack. We don't know how or when the original Madonna was lost, only that the present one was installed in 1330, replacing an earlier one.⁷

An old print showing the chapel on the Kapellplatz with the linden tree next to it, its wide branches supported by a structure.

The Black Madonna of Altötting did not reach widespread fame until 1489. What happened that year? The book 'Mary is Our Refuge', written in 1497, reports that a three year old boy fell into a stream and floated in it for half an hour until he was pulled out "completely dead." The distraught mother, with great trust in the Virgin, carried the dead child to the holy chapel and laid it on the altar. With her companions she fell on her knees and begged for the revival of her child. Immediately her son came back to life.

Soon another miracle happened: A farmer, returning home from the fields with a horse drawn wagon full of grain, had set his six year old son on the horse. The boy fell off and under the wagon. He was crushed so badly that there was no hope for his life. But the family made an oath and called upon the Mother of God. On the next day the boy's health was restored one hundred percent.⁸

News of the intercessory power of Our Dear Lady of Altötting spread like wild fire and soon hundreds of thousands of pilgrims started coming each year from all over Europe. To this day Altötting receives about one million pilgrims annually.

Our Dear Lady of Altoetting without the outer robes. Photo: Foto-Strauss

We don't know when the title Black Madonna was accorded Our Dear Lady, but according to Brigitte Romankiewicz, she was already invoked as a Black Mary during the 30 Years War in the first half of the 17th century. This was also when King Maximilian of Bavaria consecrated himself and his country to the Virgin of Altötting by writing her a letter, using his own blood as the ink. (This "blood-consecration-letter" is still kept in the base of the tabernacle under the Black Madonna.) Since then the hearts of the kings of Bavaria, including Emperor Karl VII, have been set to rest in this 'chapel of grace', keeping a sort of royal honor guard.

While the Madonna and her whole little chapel were likely blackened by centuries of candle soot, people apparently valued the mystery of her darkness so much that in 1630 they painted the inside walls and ceiling of her chapel black.⁹ Now all who step inside this small, round, windowless, sacred space, as it were enter the dark, nurturing womb of their Heavenly Mother.

If you visit Altötting you may want to pay respect to the local saint. Brother Konrad of Parzham was a 19th century monk, who led a very humble life of deep faith as the gatekeeper of his monastery. In that function he gave what ever help he could to whomever knocked on the doors of the monastery whether they were looking for bred, shelter, advice, or blessings. He was famous for his devotion to his heavenly Mother. He obtained the privilege of serving at mass in her 'chapel of grace' every morning, of spending another hour in prayer before her later in the day, and of often offering her flowers.

You'll find his monastery, Kapuzinerkloster St. Konrad, if you head towards the big St. Anna basilica. His cell and tomb can be visited. In front of it you will also find the "Pope-Linde", which Pope John Paul II planted.

Those who look for connections between Black Madonnas and Mary Magdalene might be interested to know that one of the churches on the place surrounding the 'chapel of grace' is dedicated to St. Magdalene. It was first consecrated in 1591, then rebuilt in 1700 and is part of a Jesuit monastery. The guide says, a tour of this beautiful monastery is not to be missed.

Footnotes:

1. See: Halle, Belgium, Neukirchen-beim-Heiligen-Blut, Germany, Monte Civita, Italy, Antipolo, Philippines, etc.

2. E.g. in Telgte, Münsterland, and Sulzberg, Austria.

3. See: the www.de.wikipedia.org article on "Altötting", under the heading "Kelten, Römer, Bajuwaren" and Stefan König, Altötting: Wallfahrts- und Stadtgeschichte, Verlag St. Antonius Buchhandlung, Altötting: 2008, p. 29.

4. Ibid, p.25

5. See: Luigi Accattoli's, When a Pope Asks Forgiveness: The Mea Culpa's of John Paul II, Pauline Books & Media, Boston: 1998.

6. While no written record of this event exists, the first extant mention of Altötting as the seat of the duke stems from 748 A.D. (not much later) so there is no reason to doubt the oral tradition. See: Altötting: Wallfahrts- und Stadtgeschichte, op. cit. p. 12 and 29. The octagon is associated with Christian baptismal fonts and chapels, the number 8 symbolizing rebirth.

7. Ibid. pp. 15 and 32.

8. These medieval accounts are quoted in Brigitte Romankiewicz, Die schwarze Madonna: Hintergründe einer Symbolgestalt, p. 44

*9: Altötting: Wallfahrts- und Stadtgeschichte, op. cit. p. 31.