Lluc, Majorca

In her sanctuary, 61cm, stone, original at least 13th century.

Mother of God of Lluc (Catalan: Mare de Deú de Lluc)

Dear Dark One (La Moreneta)

Patroness and Queen of Majorca

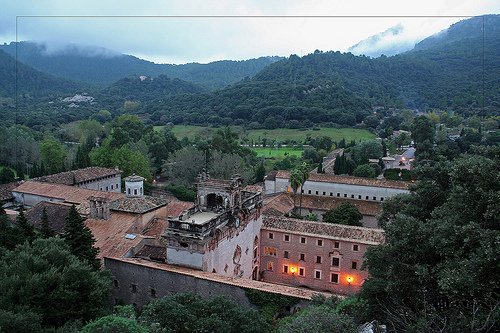

Inland and up in the Tramuntana mountains, the sanctuary of Lluc not only lays in the physical center of Majorca, but also is the spiritual center of the island. The place may have been sacred for many millennia, for near the sanctuary the remains of a prehistoric settlement have been excavated, known as la Cometa dels Morts. The Romans also held the place holy, calling it Lucus, that is ‘sacred woods’. In the Arabic language of the medieval Muslim settlers ‘Lucus’ became ‘Al-luc’, which became Luc and then Lluc when the Christians had re-conquered the isle.

Though the Queen of Majorca doesn’t look that dark in this picture, there can be no doubt that she is officially a Black Madonna. It says so right on her halo, though it’s hard to see: “Nigra sum sed formosa”. This quote from the Song of Songs means “I am black but beautiful”. For more on its significance in the context of Black Madonnas read in the introduction’s sub-heading: “the Church’s Explanations, 7.” Her blackness and her power to work miracles are also attested in the museum (open daily 10-5), adjacent to her sanctuary.

Photo: a great flickr photographer

A folk tradition explains why the Madonna is called Our Lady of Lluc, why she is so dark, and why her shrine lays in a remote area. It follows many of the usual elements of a Black Madonna legend: a statue buried in the wilderness, revealed to a young shepherd by divine light, is carried into an existing church but lets people know that it wants a sanctuary for itself in a designated place in nature.

The Majorcan version of these recurring themes takes place shortly after the Reconquista (when Christian troops re-conquered Spanish territories that had been held by Muslims for centuries): An Arabic family had to hand its estate over to the new rulers of the land and had to convert to Christianity if it wanted to live. One of the sons, little Lluc (presumably Arabic for Luke) was in charge of pasturing the family’s goats and sheep on the same mountains that used to belong to them. One day he observed a strange light coming from a cleft rock. Drawn by curiosity, he climbed into the rock and found this statue of the Virgin, which barely peaked out from the earth. What surprised him most was that she was of the same dark skin color as he himself. Very excited, the young shepherd brought the treasure he had found to the parish priest of the church Sant Pere d'Escorca, 6 km away. The clergy man gave her a place of honor in his church, but by the next day, when the faithful were already flocking in to venerate her, she had disappeared. Lluc found her back in the same place as the day before and returned her to the parish church. But again she disappeared over night, returning to her mountain abode. This time the priest understood that the Black Madonna wanted to remain in the place where her radiance first revealed her. So that’s where he had a chapel built for her.

Note how the story deals with Muslim-Christian relations. It seems to express some concern over Muslims losing lands they considered their own for hundreds of years and over being forced to convert. The Madonna seems to reach out to them affectionately by revealing herself to an Arab in a skin tone closer to his than to the Spaniards. She also forces Christians to have respect for their newly converted Arabic brothers and sisters by leading one of them to her treasure. Furthermore she seems to say: “This land belongs neither to Arabic nor to Spanish lords but to me! Let this be a place where all can come and worship the Creator and his Mother.” (More on Black Madonnas and race relations in the introduction.)

So much for the legend. More prosaic people explain that Lluc means ‘forest’ in the Majorcan dialect and to this day the area is densely forested. The word comes from the Latin lucus, which originally designated a forest or grove that was dedicated to a deity. Later the word was used as a poetic term for forest. Also Spanish reconquistadores often sought to establish holy sites in well visible places overlooking newly re-conquered terrains, which may be another reason why a chapel with an important Black Madonna was built in the mountains. Ean Begg’s explanation for why the statue was buried is that she was hidden from the Muslim invaders in the 9th century.¹ However, the style of the image is gothic rather than Romanesque. Maybe the original was lost and replaced? According to Begg she was repaired in 1884 and stolen but replaced in1978.

Whether in response to real events, to a legend, or simply to a Black Madonna: so many pilgrims flocked to the place that the first monastery and hermitage was begun in 1260. It was to care for and house the pilgrims. The earliest extant record stems from 1268. The first monks to inhabit the place were Augustinians, who seem to have a special connection to Black Madonnas. (See: Chipiona) That seems befitting for an order founded by an African saint. Later a seminary was added to the compound and now the Missionaries of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary are the caretakers of the sanctuary.

When la Moreneta was canonically crowned in 1884 more than 12,000 people attended the festivities.

Reminiscent of Montserrat, one of the sanctuary’s main attractions is its children’s choir, which was founded in the 16th century and is called the Blauets. Only Lluc’s choir seems to include girls. On Christmas Eve one of them gets to impersonate a sibyl (pre-Christian female oracles who supposedly prophesied the coming of Christ). She performs an ancient ceremony and ‘Chant of the Sibyl’ that only survives in Alguer and Majorca. On ordinary days the choir sings the Salve Regina prayer to Mary in the mornings and evenings before the Black Madonna.

Although her official feast day is the 12th of September, since 1974 an annual pilgrimage takes place on the first Saturday night of August. The 48 km walk is known as ‘the march from Güell a Lluc’. Often more than 10,000 faithful set off from Plaça des Güell in Palma de Mallorca at 11 p.m. They walk all night and arrive at the sanctuary some time the next day.

Footnotes:

1. Ean Begg, The Cult of the Black Virgin, Arkana: 1985, p. 256.

Much information for this article was gleaned from: http://www.mallorcaweb.com/reportajes/monasterios-y-santuarios/santuario-de-lluc/ , and http://www.serviciocatolico.com/files/virgen_de_lluc.htm, and http://mallorcaphotoblog.wordpress.com/2008/08/03/the-annual-marxa-a-lluc/